This assignment has two parts. The first part asks you to analyze some simple English morphology. The second part ask you to analyze the structure of some Penn organization names, in two diferent ways.

1. English Morphology

The abstract of a biomedical article is given below. In the cited abstract:

1(a) List all the instances of regular inflectional suffixes. In each case, give the base form, the category of the base form, the suffix, and the inflected form.

1(b) List all the instances of derivational suffixes that are at least semi-regular, in the sense that the putative base form exists as an independent word with a plausibly related meaning, and the pattern of derivation corresponds to other examples in the language. In each case, give the base form, the category of the base form, the suffix, the combined form, and the category of the combined form.

1(c) List all the instances of derivational prefixes, following the same criteria.

The year 2011 marked the half-centenary of the publication of what came to be known as the Anfinsen postulate, that the tertiary structure of a folded protein is prescribed fully by the sequence of its constituent amino acid residues. This postulate has become established as a credo, and, indeed, no contradictions seem to have been found to date. However, the experiments that led to this postulate were conducted on only a single protein, bovine ribonuclease A (RNAse). We conduct molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on this protein with the aim of mimicking this experiment as well as making the methodology available for use with basically any protein. There have been many attempts to model denaturation and refolding processes of globular proteins in silico using MD, but only a few examples where disulphide-bond containing proteins were studied. We took the view that if the reductive deactivation and oxidative reactivation processes of RNAse could be modelled in silico, this would provide valuable insights into the workings of the classical Anfinsen experiment.

Note that you should ignore cases where an English word inherits frozen derivational morphology from its etymological source, without a clear meaning relation between the (historical) base and the derived form, even though the same morphemes may be active in other words in English. An example (not found in the cited abstract) is prescribe, which comes from Latin praescrībere, from prae- (“before, in front”) and scrībere (“to write”) -- where the same Latin verb also underlies English subscribe, describe, ascribe, etc. The meanings of those words have drifted far enough that no clear shared sense of -scribe emerges. And so even though pre- is an active derivational prefix in other English words like preheat or pre-war, you shouldn't include prescribe (if it was found in the abstract) in your list of derivational prefixes.

However, many words are what we might call "semi-frozen", where the derivational relationship seems clear, but the morphemes change in an irregular way. An example is the relation of prescribe to prescription, where the meaning relationship is clear, but both the base form and the suffix have "allomorphs" that are hard to predict in English, though they were (more or less) regular in Latin. Such cases should be included in your list. If a particular example seems marginal to you, say so.

Note also that chemical nomenclature has its own complex and semi-artificial rules. For example, monoxide is mon + oxide. And oxide is a (semi-)frozen blend (originally from 18th century French) of ox(ygene) and (ac)ide. The -ox- part evokes oxygen, just as the -chlor- in hydrochloric or perchlorate evokes chlorine; and -ide has similarly been adopted and re-used as part of the complex system of chemical nomenclature, as in chloride and fluoride. There are a few examples of such morpho-chemistry in the cited abstract, and you should include them in your list.

2. Syntax of Penn Organizational Names

Penn's organizational names are all noun phrases. They may simply be "complex nominals", which are a sequence of one or more modifying words (usually nouns or adjectives) preceding a head noun, such as "Admissions Office" or "Annenberg Public Policy Center". Some organizational names may include prepositional phrases and/or conjunctions, like "Perelman School of Medicine" or "College Houses and Academic Services" or "College of Liberal and Professional Studies".

Showing structure with parentheses

In the examples below, use parentheses to indicate the structure of each phrase. Use a "binary bracketing" -- that is, add parentheses in a way that always groups words or word sequences in pairs. Note that your parentheses must always balance -- every left parenthesis must always have a corresponding right parenthesis somewhere, and vice versa. Each pair of parentheses surrounds a subexpression.

Answers are given for the first four examples.

- Ancient Studies Center ((ancient studies) center)

- Biology Graduate Group (biology (graduate group))

- Penn Language Center (penn (language center))

- Annenberg Public Policy Center (annenberg ((public policy) center))

- Pennsylvania Muscle Institute

- Plant Science Institute

- Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board

- Wharton Real Estate Center

- South Asia Regional Studies Department

- Perelman School of Medicine

- College Houses and Academic Services

- College of Liberal and Professional Studies

- Center for High Impact Philanthropy

- Center for Programs in Contemporary Writing

- Clinical and Translational Research Center

- Greenfield Intercultural Center

- Leonard and Madlyn Abramson Family Cancer Research Institute

- Office of Alcohol and Other Drug Program Initiatives

- Environmental Health and Radiation Safety Office

- Monell Chemical Senses Center

Showing structure with trees

Your next task is to represent exactly the same structural analyses with constituent-structure trees, adding two more pieces of information: the part-of-speech tags for the individual words, and the categories of the higher-level nodes (corresponding to parenthesized groups in the preceding section).

You can draw the trees by hand, or (better) use an app like this one.

Parts of speech and node labels

For this exercise, you'll need to use these part-of-speech tags (labelling individual words):

| POS Tag | Name | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| CC | "Coordinating Conjunction" | and |

| DT | "Determiner" | the |

| IN | "Preposition" | of, for, on, in |

| JJ | "Adjective" | ancient, applied, human |

| NN | "Singular Common Noun" | health, research, computer |

| NNS | "Plural Common Noun" | disorders, sciences, writing |

| NNP | "Singular Proper Noun" | Philadelphia, Perelman |

And these phrasal node labels

| Node Label | Name |

|---|---|

| NP | "Noun Phrase" |

| PP | "Prepositional Phrase" |

(Of course, analyzing more general material would require more POS tags and more node labels...)

Some examples of how to use those tags and node labels

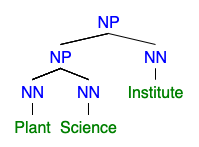

Using the cited on-line tree-drawing app, this input

[NP [NP [NN Plant] [NN Science]] [NN Institute]]

produces this output:

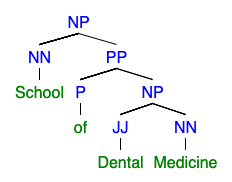

This input

[NP [NN School] [PP [P of] [NP [JJ Dental] [NN Medicine]]]]

produces this output:

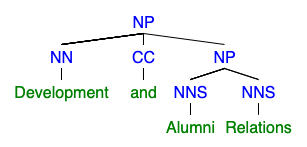

This input

[NP [NN Development] [CC and] [NP [NNS Alumni] [NNS Relations]]]

produces this output: